I was raised to believe that love – primarily maternal, in this sense – had to be earned.

The hugs felt a little warmer when the grades were good. The beaming sense of pride felt a little brighter when I managed some athletic feat. The sense of serenity felt a little more secure when my room was tidy and everything was in its place.

Unfortunately, I was a child that didn’t see the purpose of grades. I loved to eat. And, with my nose in a book and my mind in la-la-land, neatness wasn’t a priority.

“DON’T BE A FAT SLOB.”

“WELL, THAT WAS STUPID. DON’T BE STUPID.”

I would have been happy if this had come from a bully. I had the acerbic wit and sharp tongue1 to deal with my peers. But coming from your mother? The soul that was supposed to be one of your closest allies in this game called life? The only comeback I had for that was silence, withdrawal and, on occasion, tears.

– – –

My mother had a way of bouncing between states of pure love and raw anger. The former was characterized by selfless surrender, sacrifice and tenderness. The latter was characterized simply by verbal tirades.

Messes and mistakes seemed to be the things that would set her off on a consistent basis. A spill of any colored liquid on the kitchen grout, for example, could set off a fury that would immediately turn the room from joyful to nervous. “GODDAMMIT, YOU BETTER PRAY THAT GROUT ISN’T STAINED. (Turning to no one in particular) SON OF A BITCH!” And as we’d scrub away furiously or try to put things in order, the haranguing would persist. On many occasions, the virulence of the yelling would bring myself and/or my siblings to tears. I didn’t know why I cried, I just knew this wasn’t supposed to be like this.

Of course, the situation would be ameliorated minutes, hours or days later with the softest of expressions. “I’m sorry for what I said, I just got very upset. You guys make mistakes sometimes and I get angry.” And all would be okay with the world again, at least superficially.

Even at that age, I knew that I didn’t have it bad. A lot of people don’t have mothers. A lot of people have mothers that are too emotionally destructive to be able to provide for their basic needs. A lot of my friends’ mothers were much more caustic and dismissive than my own. My mother did give us words of love and encouragement.

But it was never about the tenacity of the words so much as the uncertainty of the emotion that stuck with me. I never knew whether I was going to get attentive, loving mom or angry, inexorable mom.

Around the sixth grade, I got this bright idea – “do what makes your mom happy and then maybe you’ll get more of the version you like.” So for the first time in my life, I got honor roll. Holy shit! I was so impressed at myself for being able to buckle down, focus and nail it.

I tra-la-la-la-laed all the way home, knowing she was going to adore that ‘My Kid Is An Honor Student’ sticker she had longed for. I whipped out my report card, probably the first one in my life that I didn’t try to hide, and gave it to her with a Cheshire Cat-sized grin.

I vividly remember the sinking feeling – first my face, followed by my heart – as she looked up from the paper, said “this is fine, but how come these aren’t all As? They should be all As,” turned and walked off.

On the surface, I expressed nonchalance. Deep inside, in a place I couldn’t quite reach at the time, I lamented “If not this, then what??”

– – –

Throughout my teens and 20s, this angst morphed into a deeply rooted sense of anger. Unconsciously, I realized that I was no longer a child and thus no longer powerless to the situation. Not having yet addressed that anger, however, I chose to use that power to fan the raging flames of discord.

After I moved to London, I saw her only once a year. That time and space melted any superficial ice. Our time together would kick off with an abundance of joy. But then, often around day 10 of a 14-day visit, something would set one of us off. And because of that newfound sense of “power”, I was always more than keen to fire verbal arrows right back. I was quick to point out the hypocrisy of being an angry Catholic, to poke at awful emotional truths that were none of my business and, on occasion, to simply blurt out the words “you’re a shitty mother.”

The ability to cause her hurt filled my veins with this icy, invigorating, almost intoxicating sense of control. And yet, I felt strangely out of body in those moments. I could feel something deep inside also saying “As hurt as you are, this isn’t you. You love your mother and you love others, even if you don’t agree with or feel loved by them.”

I started going to therapy in 2013. By then, it was becoming clear that I was a textbook Freudian case in transposing some deep-seated anger towards my partners. I chuckled at the idea that having a shrink would only cement my status as a Manhattan-ite.

By session two, all signs pointed to a strained mother-son dynamic. I had seldom shied away from sharing these frustrations with others. Yet, I hadn’t realized how much it truly hurt me, then and in childhood. I wanted to pretend like all I harbored was anger and annoyance. But below that was a deeply wounded, confused child.

I never was able to make sense of the situation. Here was a person who clearly loved and adored her children and taught them so many good values, yet could easily turn on a dime and make them (perhaps just me) feel unloved. I craved acceptance and love from my mother for who I was – slight weight issues, bookworm tendencies and all – and because I had operated under this idea that I was only loved if I did good, the love felt absent in my heart.

To deal with this, I had harbored a sense of feigned detachment and machismo. I didn’t want to fucking cry over my mom, I was a man. I didn’t want to be so emotionally vulnerable, I was a man. We’re supposed to suck this shit up, right?

But in doing all of that, I wasn’t being a man. I was being something I wasn’t. You can’t fake manhood. And the entire time, my true self yearned to emerge, so it could finally grow into the man it longed to be. Tender, honest, strong.

Over time, I started opening up to my mother about the anger I’d felt towards her. Naturally, we fought about it. She wanted me to not spend time dwelling in the past, but I told her that I had to be able to look at it head on in order to make peace and let go. She acknowledged, as she had on many occasions, that she didn’t want to be angry at us and that she was hurt by the idea that I felt unloved.

As both of our defenses softened and we saw the deep sense of love that sat beneath it all, our relationship grew warmer. I looked at the past not as a series of traumatic episodes, but as a necessary path to becoming the curious, wanderlust-filled person I had become.

My relationships with others blossomed as well. Yet, all was not well in Camelot. I would still have episodes where an intense sense of fear would morph into anger towards my romantic partners. One could say I was acting out at them the way my mother used to act out at us. I was dismayed. I had faced the anger, I had mostly made peace with it. Why was this still happening?

– – –

Through the exploration I described in Part 1, I’ve come to learn that there is a clear correlation2 between a mother’s stress levels before and after pregnancy and the emotional health of the child.

The more a new mother is anxious, the less she is able to be emotionally present for her offspring. And because infants crave emotional and physical connection to their mothers, an extended absence of connection causes the child pain which they then learn to soothe through immediate, yet ultimately inefficient means.

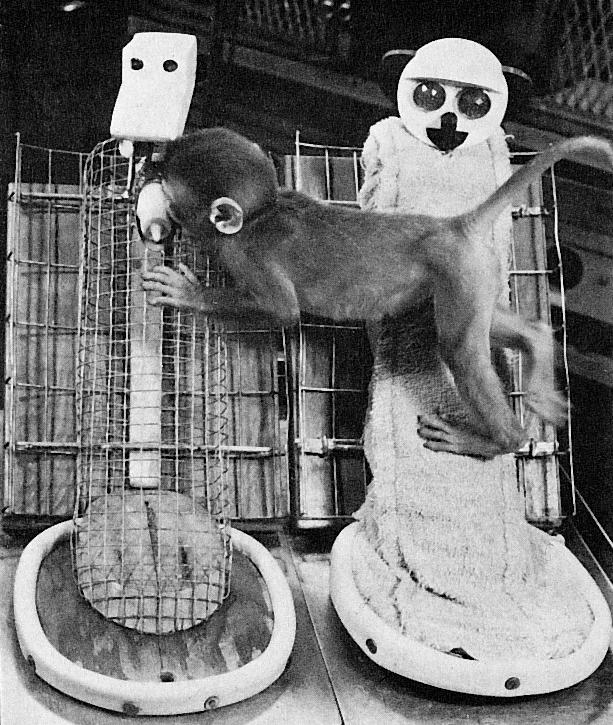

Harry Harlow’s (in)famous3 research shed a light on just how crucial the quality of the mother-child bond is to emotional development.

In one experiment, Harlow took infant monkeys from their mothers hours after birth and put them in a space with two surrogate mother figures: a ‘mother’ made from wire mesh which had a nipple that the monkey could eat from and a ‘mother’ made from terry cloth and foam, which lacked a nipple. One offered physical sustenance (i.e. food) and the other comfort.

The result? Monkeys tended to spend much more time clinging onto the soft, cuddly mother, even though they couldn’t nurse from it. The consensus was that the infant monkeys craved closeness and affection more than warmth or sustenance.

Ultimately, the monkeys that were raised by surrogate ‘mothers’ were much more likely to engage in strange emotional behaviors later in life. Inability to function well with the opposite sex. “Machinations that resembled stereotypical behavior patterns for excessive and misdirected aggression. “

Oh shit.

Now I’m no monkey in a lab, but it wasn’t until I did this sort of reading that I finally started to wonder – what did happen in those early years? What was my mom’s state of mind like?

I had heard occasional stories about my father being absent or gallivanting in soccer fields and bars. I knew it had been difficult. I knew there was some grief. But I knew little beyond that.

All this time, I had looked at things almost solely from my experience – but what about her experience?

It’s kind of weird to ask your mom to open up about a potentially painful period of her life. Where do you begin? How do you have a candid, empathetic conversation? It started with a deep breath, a little courage and a simple question:

“What was your childhood like?”

– – –

My mother grew up in a home where individual dreams were to be set aside for the collective good. As one of the older lot in a migrant family of eight, she had to shoulder a lot of adult responsibilities at a young age.

Weekends? Nuh-uh. Everyone has to go work in the fields. After school activies? Nope. Someone’s got to watch your sisters. Field trip day? You mean Free Babysitting day.

She loved school. She enjoyed learning and she excelled, earning impeccable grades. She dreamed of going to college and being a doctor.

College? You’re crazy. You need to work.

She dropped out of high school in spite of her passion because of her dismissive parents and because of bullying from classmates who teased her for being a goody two-shoes.

So she went to work. After some stints in nursing homes (where, according to my friends’ mothers, she earned a reputation for being a no-nonsense ass kicker), she joined an apparel company as a seamstress.

Somewhere in her mid-20s, she remembered her dream of working in the medical field. Thus, she resolved herself to becoming a Registered Nurse via the arduous, grueling path of night school.

Shortly after, life decided to intervene in the form of a charming 5’8 electrician-cum-soccer player. My father.

In a short time, my mother found herself pregnant by a man she was only somewhat romantically involved with.

Pregnancy out of wedlock? Not to be tolerated in a deeply Catholic household. My grandmother threw her out of the house for a brief spell.

Frantic, my mother called my father for help. Living with his own mother, he wasn’t able to help her. Sorry, he said.

So, there she sat. In a parking lot. Carrying an unborn child. No home to go to. Can you imagine the stress levels at that point?

She snuck back in the house at night and after a few days was welcomed back. All the meanwhile, the cortisol flooding her veins was going straight into the umbilical cord.

I was born. My father and mother were still close, yet nowhere near committed. My father showed up and took care of me, but my mother did most of the heavy lifting. Work all day, an hour or two to tend to the child, then night school.

My mother’s situation was far from stable. My father was involved in our lives, but he had other romantic pursuits. She was on edge. Was he or wasn’t he going to be a father and a husband? As is the case for most humans, her fear transformed into frustration, jealousy and anger.

My mother found herself pregnant once more. My father was still uncommitted. My mother worried. The point at which she would have to cut bait was approaching.

She sought her mother’s council. What did she say?

You can’t be a professional and a wife/mother. You’re silly for thinking you can have a career. You should have a husband.

My mother saw the pain that not having a father was inflicting on her sister’s children. So, once more, she gave up her dream of the medical field and resolved to get things in order.

– – –

I never realized my mother’s adolescence had involved so many remnants of broken dreams. I never realized she had juggled so much, had dealt with so much and had to set so much aside to make things work. In seeing those things for the first time, my heart softened.

My mother’s priority was rightfully to ensure that I got the physical cares I needed. Food. Shelter. Warmth. All of the things that her parents worked even more tirelessly to give to their children. In comparison to the previous generation and many of her peers, she was nailing it.

On the other hand, I was born a sensitive child. I craved connection and emotional presence that, because of the extenuating circumstances, could only be dispersed in varying amounts and times.

My mom wasn’t emotionally distant because she was a shitty mother or because she didn’t love me. My mom was emotionally distant because she had limited time, energy and resources and she was doing the best she could with what she had in front of her.

As for the anger lobbied towards us RE: weight, grades and cleanliness? She didn’t want us to endure teasing like she did; she didn’t understand why we wouldn’t get straight As considering the freedoms we had compared to her; and she wanted us to always put our best foot forward.

It’s hard to build a complete picture unless you get multiple sides of the story.4 In putting the pieces of my infancy together, I began to see how my emotional development could take shape in a manner that wasn’t quite conducive to my own well-being, in spite of an otherwise loving family dynamic.

Over time, I came up with an analogy to better explain my situation:

Imagine you lend a friend your car. The next day, your friend tells you that they were drunk and totaled your car.

Shit, you needed that car to get to work, run errands, etc. Your life has become that much more complicated.

How would you feel? LIVID might be an appropriate answer. You wonder how your friend could have been so careless?

But what if your friend tells you “I was out late, walking by myself and a strange man started following me. I didn’t know what to do. I felt frightened. I ran to the car and drove off because I needed to feel safe.”

Oh my god. That changes things. You’re probably a lot more sympathetic. You want your friend to be safe, you can relate to that sort of fear and, at the end of the day, it’s a car. You forgive your friend.

It doesn’t change the fact that you still don’t have a car. You are without your functioning vehicle and, thus, have to resort to other, likely inconvenient, means. Doesn’t matter how at peace you are with the situation. You are working from a disadvantage.

In other words, I could make all of the peace in the world with my mother, my partners and myself. It doesn’t change the fact that I have this mental wiring that is a bit clunky, doesn’t do well with being alone and often reacts from a place of fear or anxiety, rather than calm.

That said, doing the work to understand the potential sources of my emotional tumult – whether it be texts on brain development or just listening to my mother share her tender experiences – has given me two things that have made living with this #crazybrain (as I like to call it) much more joyful: acceptance and awareness.

I’ve come to accept that my mother did her best and meant no harm, in spite of what I carry. I’ve come to accept that things will never quite be perfect between us5, but that we share a sense of love, concern and care that will always unite us. I’ve come to accept that, no matter my intentions, that there will be moments where my brain’s circuit breakers aren’t tripped and a surge of Dumb Shit will come flying out. I’ve come to accept that I’m going to fuck up sometimes, but that does not make me a fuck up.

I’ve come to accept the fact that I may not be able to completely re-wire my mind – but I do also know that the brain is amazingly malleable. That’s where awareness comes in.

Knowledge was the first step. Tying loose emotional ends was the second. The third – and most arduous, yet most rewarding – step has been coupling the first two into a practice that enables me to be more aware of when these moments arise and be able to make more conscious, productive decisions.

Awareness – in the form of mindfulness and meditation – was unexpected. But it was the piece that tied all of the lessons of the Dumb Shit discovery together in order to create something productive. And it just happened to be the first piece in a surprising journey into my inner, more wild (dare I say hippie?) self.

– – –

1I have to acknowledge my own culpability in these interactions. Once I learned that a biting comeback earned you laughter, acknowledgement and maybe a smidge of esteem, I started baiting people to then deliver verbal blows. I crossed that smart ass/bully line quite a bit.

2Since this is a bit of a strong claim, it’s probably best that I cite a few sources, right? Here’s a detailed research paper from the National Institute of Health, a summary of Harry Harlow’s work and, of course, The Realm of the Hungry Ghost by Dr. Gabor Mate.

3I admittedly have mixed opinions on Harry Harlow. His work involved putting quite a bit of primates through severe emotional trauma, something he was unabashed about.

“The only thing I care about is whether a monkey will turn out a property I can publish. I don’t have any love for them. Never have. I don’t really like animals. I despise cats. I hate dogs. How could you like monkeys?”

I am grateful for his unraveling of the mysteries of the human psyche. But goddamn, what did the monkeys – or other animals, for that matter – ever do to deserve that treatment?

4I spoke with my father as well. Of course, his depiction varies somewhat from my mother’s, but isn’t that always the case?

5Just the other day, I got snippy with my mother for wanting me to “not be sad” about letting go of a past relationship. As I’m always quick to point out, “If happiness was a light switch, don’t you think I would always have it flicked to on??”

Excellent as always buddy!

LikeLike

Awesome to read as a mum, as a daughter and knowing you too. Thanks Daniel x

LikeLike